A MultiCare physician is leading efforts to prevent the premature deaths of police officers, firefighters, airline pilots and soldiers, along with others in high-risk jobs.

“Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death in this population, and their work — stress, physical activity, etc. — is thought to be contributory to the cardiac-related issues. Thus, special guidelines need to be developed for screening and treatment of this at risk population,” explained Matthew Budoff, MD, when asked about the importance of the work. He is a professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a nationally known cardiologist featured in the Netflix documentary “The Widowmaker.”

So a group of physicians and others from around the country have been working online for over two years to develop a working paper that will — hopefully — lead to lifesaving guidelines.

The lead author on the paper, which was published in April, is cardiologist Ahmad Slim, MD, regional chief medical officer for Pulse Heart Institute in Puget Sound.

What’s driving the work is a strange but true finding: the people in high-risk occupations who are most likely to die from a heart attack are the people who, based on current medical diagnostics, appear the least likely to die from heart attack.

No wonder people are dying young.

Dr. Slim learned this on the job when soldiers around him were falling.

“I just wanted to do something”

Two weeks after on the Sept. 11, 2001 airplane attacks on U.S. landmarks Dr. Slim, then a medical resident, enlisted in the Army.

“I just wanted to do something,” he said.

The original plan was to stay two years as a patriotic act. Instead, he stayed 12.

“I enjoyed the military. I thrived in the military. I owe a lot of my career to the military. I love the camaraderie and the folks I took care of,” he said.

Dr. Slim worked from Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, where the Army concentrates its cardiologists. He was asked to help with research to determine how to identify whether soldiers had healthy enough hearts to be deployed.

Along the way, he and other team members ran the numbers and found out something very startling. Sudden death from cardiac events killed more soldiers than enemy attacks and suicide.

Cardiac events also kill a relatively high number of firefighters and police officers compared with other causes, he said.

“Very early in my career, I was one of those who determined that whatever we’ve been doing to determine risk of sudden cardiac death, it wasn’t working,” Dr. Slim said. “So that took me down the path of trying to identity why that is. Once you go down that path, you don’t come back. We need to know.”

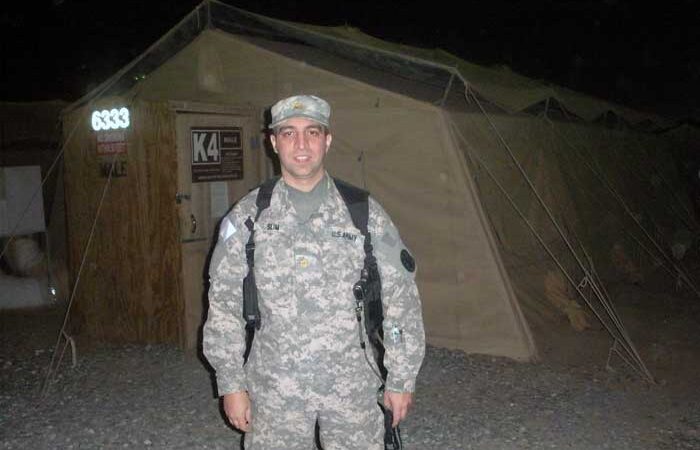

Dr. Ahmad Slim’s interest in preventable death came from many years with the military; here, he’s seen in 2011 outside a tent in Kuwait before entering Iraq.

What are we missing?

“We know that cardiac events present a risk to people in high-risk occupations, but none of the current scoring or testing systems are doing enough to identify these people in advance,” Dr. Slim said. “It’s partly because with the current paradigm when we calculate risk scores, we don’t calculate a risk for being in a high-risk occupation.”

One potential issue with current testing: People often begin careers in high-risk occupations when they are young, and the plaque inside their veins is softer than it would be in an older person. That makes the plaque harder to detect with traditional testing methods. But that young person, by being in a high-risk occupation, is still at risk — even if the test doesn’t acknowledge that risk.

Many of these people don’t have significant obstructions you can see on a treadmill test, Dr. Slim said. The treadmill test tells you that a person is physically fit; but the person might also have mild blockages. Those blockages might not increase heart attack risk for many of us, but may cause a fatal attack in this particular person because of the stress of their job and other exposures.

“And so you have soldiers who are going to die in the middle of the field because you’re applying the same risk to them as someone in the general public,” he said.

The other potential issue is the human side of being in a high-risk profession. According to the paper, many people in high-risk occupations don’t report chest pain or other symptoms because they fear it could affect their job.

If there were better ways to manage people with chest pain, maybe they’d be more likely to report their symptoms, Dr. Slim said: “We want people to be able to do their jobs. But we also want to minimize risk to them and in the case of someone like a bus driver, to minimize risk to members of the public who might be on the bus.”

Collaborative and a good leader

So if the present paradigm is not doing all it can to identify cardiac risks among people in high-risk occupations, what can we do about it?

In the medical world, first you create a consensus document, which collects available information from published papers and clinical trials to get some sense of what we know and what more information is needed. Then more studies take place. There’s more discussion. Eventually, there will be formal guidelines.

In this case, the consensus document is the report that was published in April.

Dozens of people and groups — largely from the American College of Cardiology, the American College of Radiology and the Society for Cardiovascular CT — weighed in on the findings.

“Dr.Slim organized the overall group and led the writing group, leading to the culmination of the work as a state of the art publication,” Dr. Budoff said.

“Dr. Slim is collaborative, a good leader and organized, which allowed us to be successful with this project.”

The consensus document forms a baseline, if you will — and now the various groups will be inviting more people into the discussion. Dr. Slim predicts it’s going to be about five years before everyone can agree on the next phase, formal guidelines that will help establish new standards of care.

There will also be more randomized clinical trials performed based on the consensus document, including some trials led by Dr. Slim at MultiCare, as well as places where he’s an associate professor, the University of Washington and Tulane University.

Dr. Slim’s personal research efforts are focused on the military, in part because he still has active duty contacts.

“My research always has and always will focus on the military. Because you leave the service — but you never really leave the service,” Dr. Slim said.

Of course, the people with the most at stake are the subject of the consensus document — the firefighters, military personnel, pilots, peace officers and others in high-risk, high-stress jobs. Efforts are underway to involve their trade groups into this work as well.

“Almost everything I can find is fixable”

The good news, Dr. Slim said, is that there’s published evidence that current treatments — if applied correctly to someone with an unobstructed blockage in a high-risk occupation — can reduce their risks of heart attack now. And the person can still stay on the job.

“I find people in these professions are very accepting once you explain it all to them and explain what current treatments can offer,” he said.

“These people don’t want to have heart attacks. They have kids. They have families. They want to be there for them. They just want to know this won’t alter the course of their life — and most of the time, it doesn’t. Almost everything I can find is fixable. It’s rare to find something where a person can’t go back to duty.”